Chapter 4 Computing Resources

In this chapter we will describe the basics about data size and computing capacity. We will discuss the computing and storage requirements for many types of cancer-related data, as well as options to perform informatics work that might require more intensive computing capacity than your personal computer.

4.1 Data Sizes

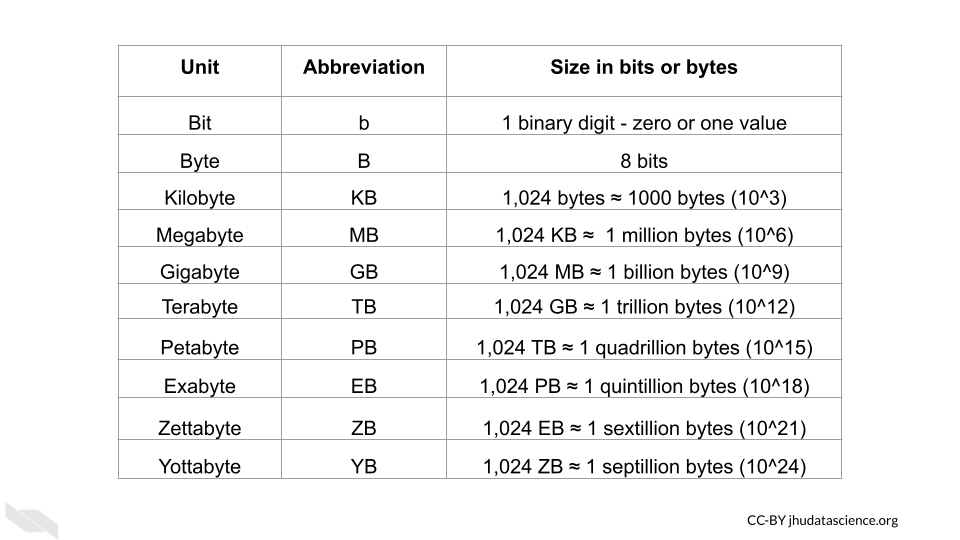

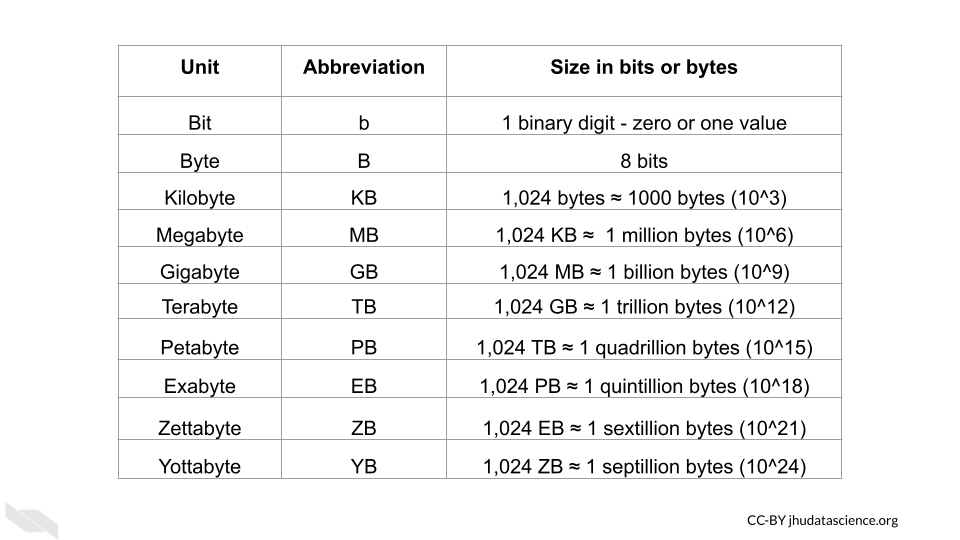

Recall that the smallest unit of data is a bit, which is either a zero (0) or a one (1). A group of 8 bits is called a byte, and most computers, phones, and software programs are constructed or designed in a way to accommodate groups of bytes at a time. For example a 32-bit machine can work with 4 bytes at a time and a 64-bit can work with 8 bytes at a time. But how big is a file that is 2 GB? When we sequence a genome, how large is that in terms of binary data? Can our local computer work with the size of data that we would like to work with?

First, let’s take a look at how the size of binary data is typically described and what this means in terms of bits and bytes:

Now that we know how to describe binary data sizes, let’s next think about how much computing capacity typical computers have today.

4.2 Computing Capacity

We have discussed a bit about CPUs and how they can help us perform more than one task at a time, but how many simultaneous tasks can the CPU of an average computer perform these days? How much memory and storage do they typically have? What size of files can a typical computer handle? These information regarding the computer’s capacity and efficiency are sometimes called the specs of a computer.

“Typical” or “average” specs of a computer will probably change very soon, and different computers vary widely, but currently:

- Laptops can often perform 4-8 CPU tasks at once, and typically range from 4-16 GB in memory and 250 GB-1 TB of storage.

This means that typical laptops can multitask quite well, have in some cases 16 gigabytes for random access memory to allow the CPU to work on relatively large tasks (as we can see from the previous table that GB are actually pretty large when you think about it), and possibly 1TB for the hard drive (and/or SSD), meaning that you can store thousands of photos and files like PDFs, word documents, etc. It turns out that 250GB allows you to store around 30,000 average-size photos, so a 1TB laptop can store quite a large amount of data. Therefore, overall, typical laptops today are pretty powerful devices, especially compared to computers of previous generations. That being said, note that some programs require 16 or even 32 GB of memory to run.

Desktops can perform and store data similarly to laptops. However, they sometimes have slightly better performance and storage compared to a laptop for a similar price. Since less work needs to be done to make the desktop small and portable, sometimes you can get better storage and performance for the same price as a laptop. Furthermore, desktops often have better graphics processing capacity and displays (Antonio Villas-Boas 2019). This might be important to consider if you are going to need to visually inspect many images. Another benefit is that you can also sometimes find desktops with larger memory and storage options right off the shelf than typical laptops. It is also generally easier to add more memory to a desktop than it is to add to a laptop (Antonio Villas-Boas 2019). However of course, desktops certainly aren’t super portable!

Some phones can compete with laptops by performing 6 CPU tasks at once and storing 6 GB in memory and 250 GB of storage.

Check out this link to compare the prices of different Macs and this link to compare specs for PC computers from HP.

If you want to get really in-depth comparisons between different PC or Windows computers, check out this link (“UserBenchmark: Core I7-11700K Build Comparisons” n.d.).

4.2.1 Checking your computer capacity - Mac

Now, what about your computer? How do you know how many cores it has or how much memory and storage it has?

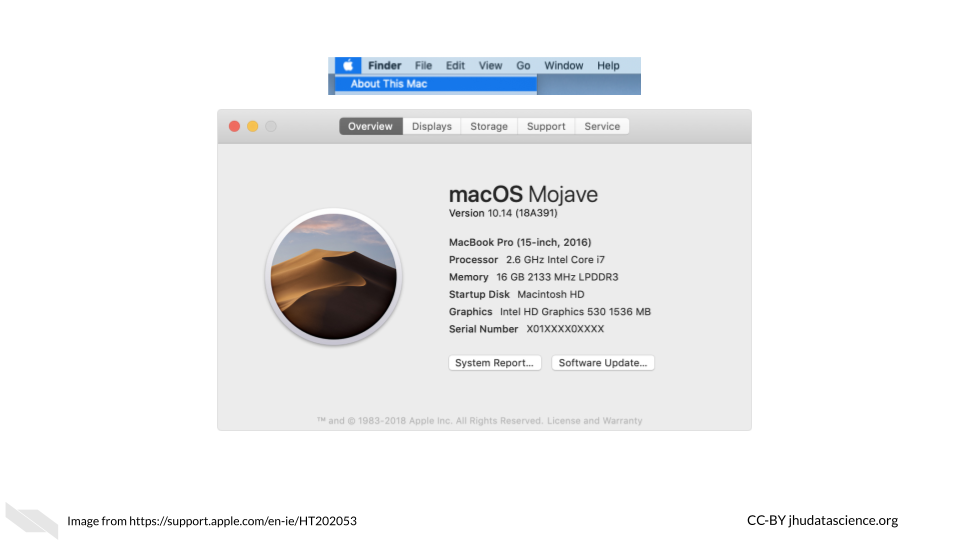

If you have a Mac, you can click on the apple symbol on the far left of your screen. Then click on the “About This Mac” button.

You might see something like this:

First, we see the operating system is called MacOS Mojave.

Next, we see that the processor (which we now know is the CPU) is a 2.6 GigaHertz (GHz) Intel Core i7 chip. This means that the processor or CPU can process 2,600,000,000 operations in a second (this is called a clock cycle) (“What Is a Clock Cycle? - Definition from Techopedia” n.d.). That’s a lot compared to older computers in the 1980s, which had clock cycle rates or clock rates in the MegaHertz range (“Clock Rate” 2021)! If we look deeper into this chip, we would learn that it has 4 cores and has hyper-threading. This allows it to effectively perform 8 tasks at once (“What Is Hyper-threading HP® Tech Takes” n.d.). Below, we see that there are 16 Gigabytes of memory - this is how much RAM it has - and also 2133 MegaHertz (aka 2.133 GHz) of low power double data rate random access memory (LPDDR3). This means that the RAM can process 2,133,000,000 commands every second (Josh Covington 2017; Mukherjee 2019). You can checkout more about what this means at this blog post Scott Thornton (2021). Generally evaluating the amount of RAM is helpful in assessing performance (Josh Covington 2017; Mukherjee 2019).

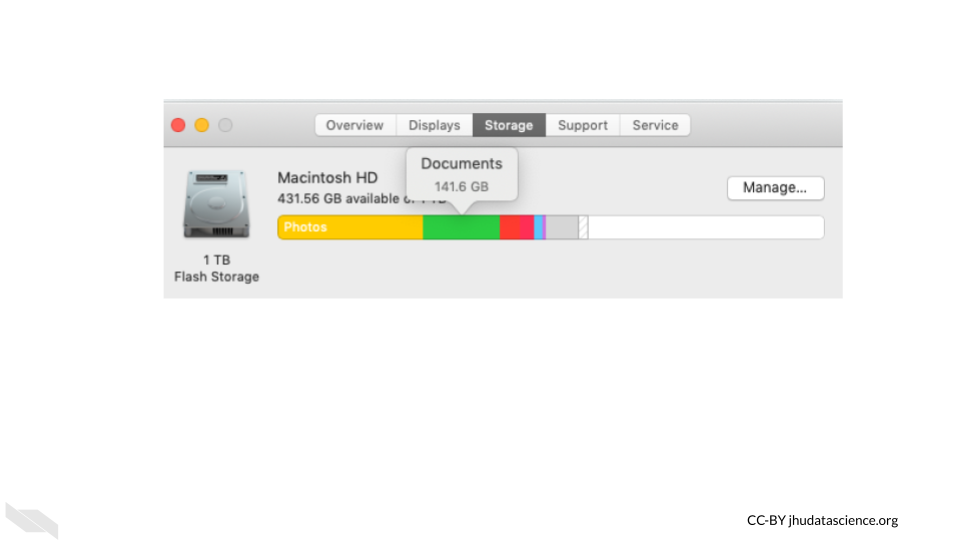

If we click on the storage button at the top, we can learn about how much storage is available on the computer. If you hover over a section, it tells you what type of files are accounting for that particular section of storage that is being used.

4.2.2 Checking your computer capacity - Windows/PC

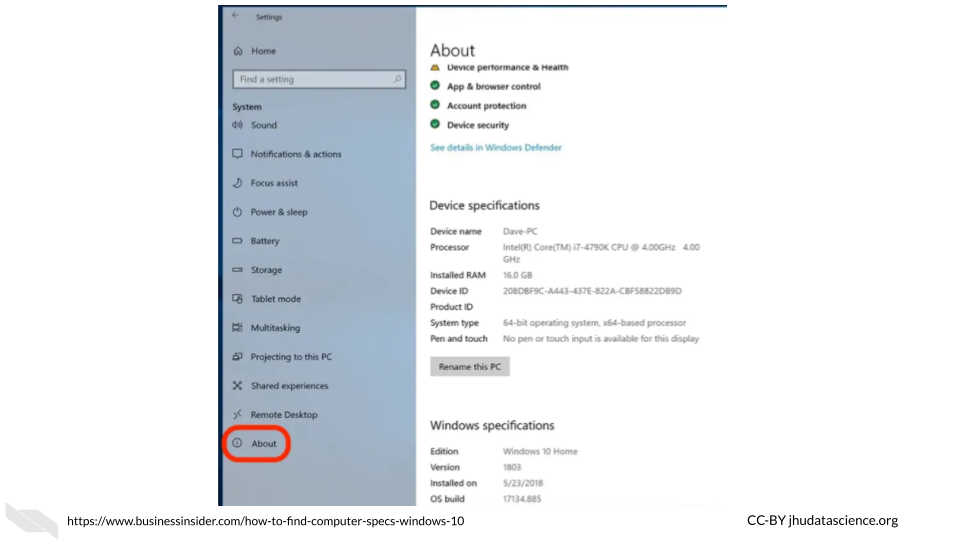

If you have a PC or Windows computer, the steps may vary depending on your operating system, but try the following:

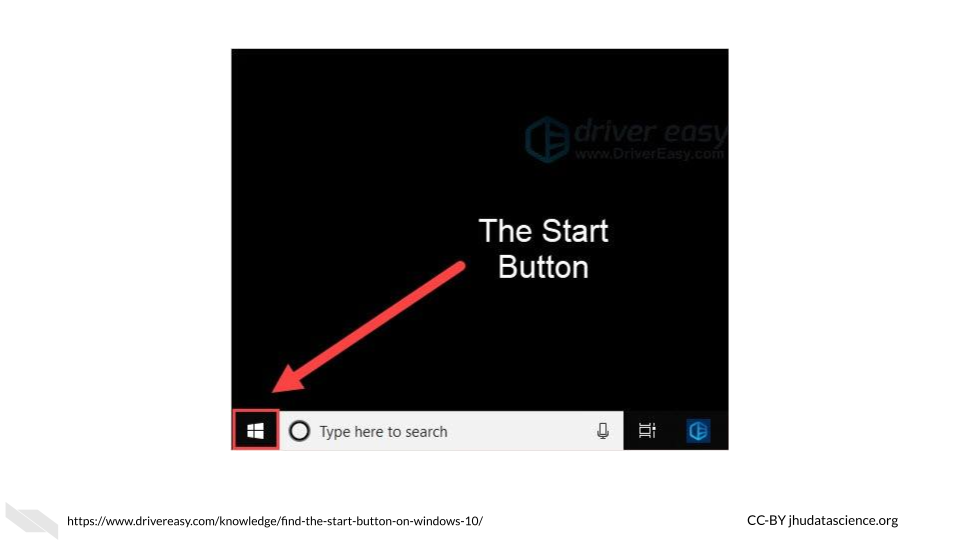

- click the “Start” button (It’s the button on the bottom left that looks like a grid with 4 squares together)

- click “Settings” button (It’s gear-shaped)

- click “System”

- click “About”

See this link for more information.

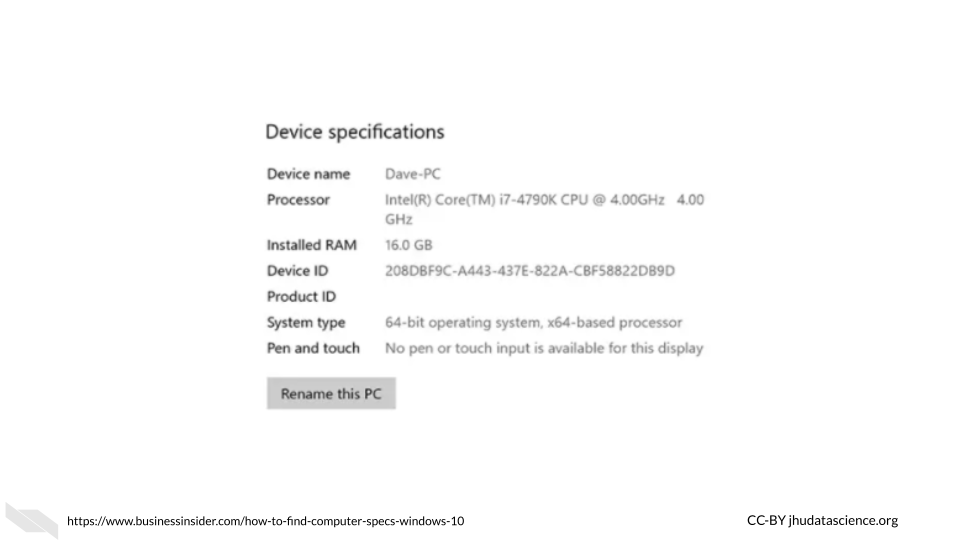

Here we can see that this computer has an Intel(R) Core(TM) i7-4790K CPU @ 4.00 GHz 4.00 GHz chip and 16 Gigabytes of RAM. If we look up this chip we can see that it has 4 cores and 8 threads (due to hyper-threading) allowing for 8 tasks at a time.

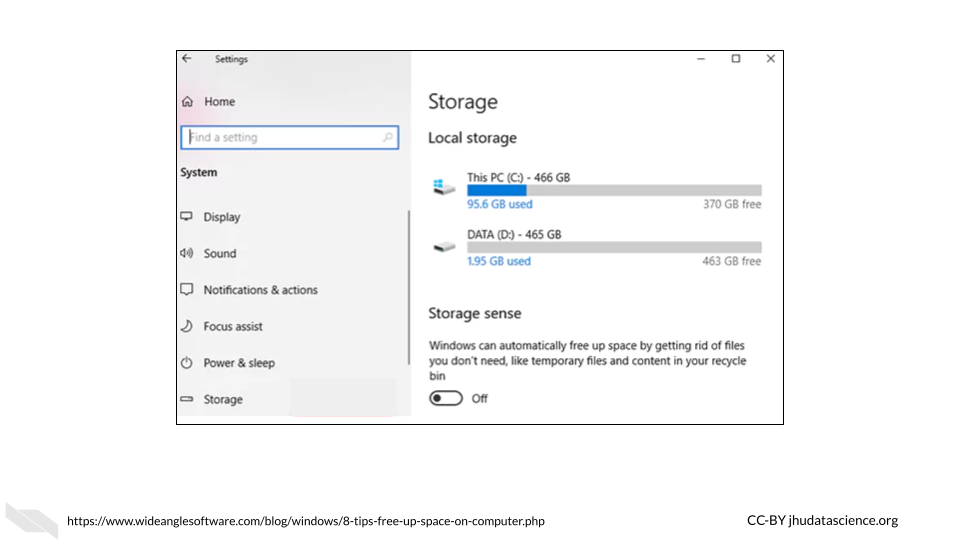

To find out more information about your storage, click the “Storage” button within the “System” tab.

Here we can see that this computer has 466 GB + 465 GB = 932 GB across the two drives. The C: drive is typically for the operating system, and the D: drive is typically where you would install application programs and save files. There are 1000 GB in a TB; therefore, we can see that this computer has about the same storage as the Mac that we just looked at.

4.3 File Sizes

Now let’s think about the files that we might need for our research, how big are files typically for genomic, imaging, and clinical research?

Recall this table from earlier about digital data size units:

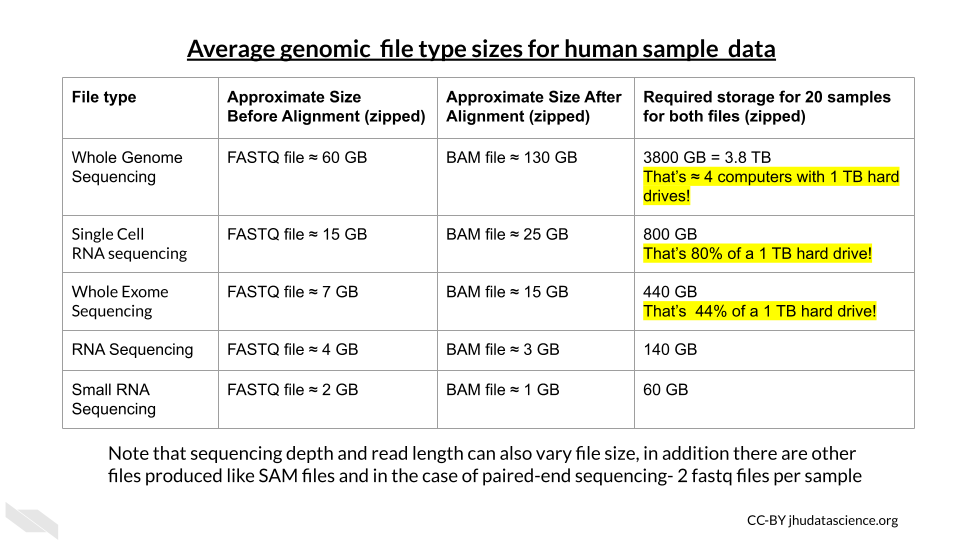

4.3.1 Genomic data file sizes

Genomic data files can be quite large and can require quite a bit of storage and processing power.

Below is a table of the approximate sizes of some common file types:

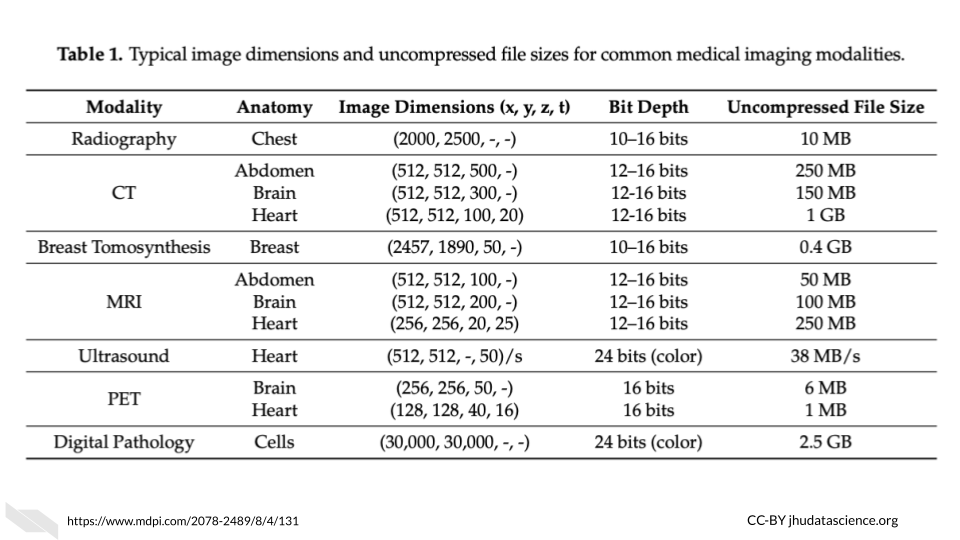

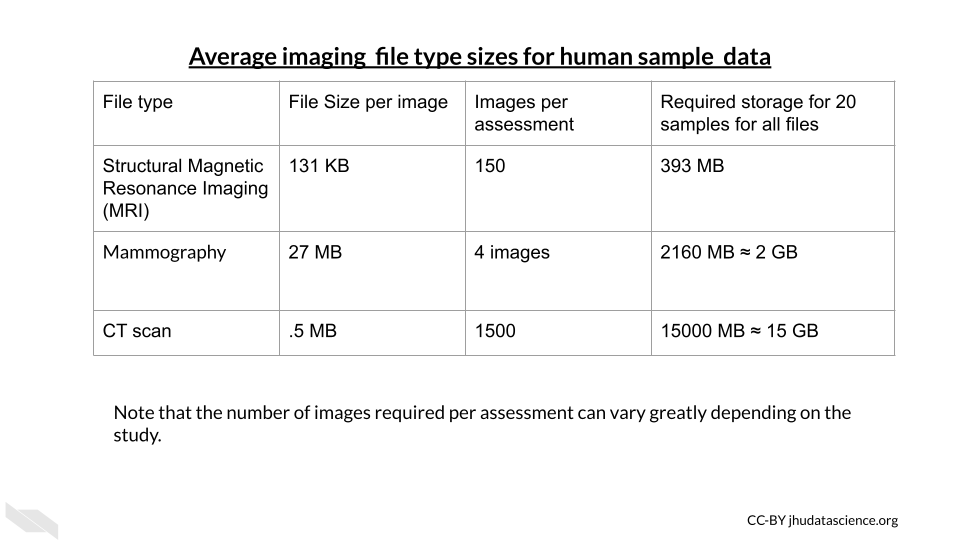

4.3.2 Imaging Data File Sizes

Imaging data, although often smaller than genomic data, can start to add up quickly with multiple images and samples.

Here is a table of average file sizes for various medical imaging modalities from Liu et al. (2017):

[source]

[source]

Note that depending on the study requirements, several images may be needed for each sample. Therefore, data storage needs can add up quickly.

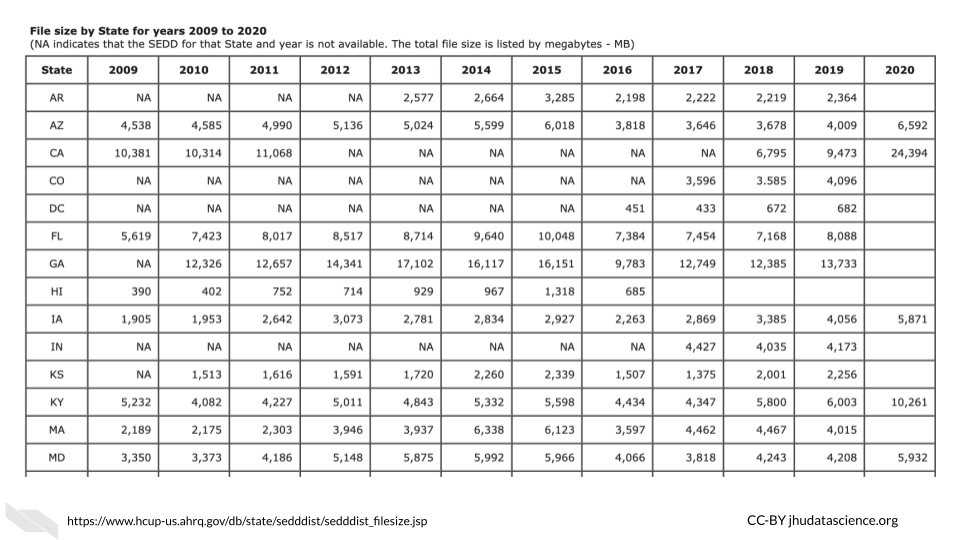

4.3.3 Clinical Data File Sizes

Really large clinical datasets can also produce sizable file sizes. For example the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) National (Nationwide) Inpatient Sample (NIS) contains data on more than seven million hospital stays in the United States with regional information.

According to the NIS website, it “enables analyses of rare conditions, uncommon treatments, and special populations” (“NIS Database Documentation” n.d.).

Looking at the file sizes for the NIS data for different states across years, you can see that there are files for some states which can be as large as 24,000 MB or 2.4 GB for California (“NIS Database Documentation” n.d.). You can see how this could add up across years and states quite quickly.

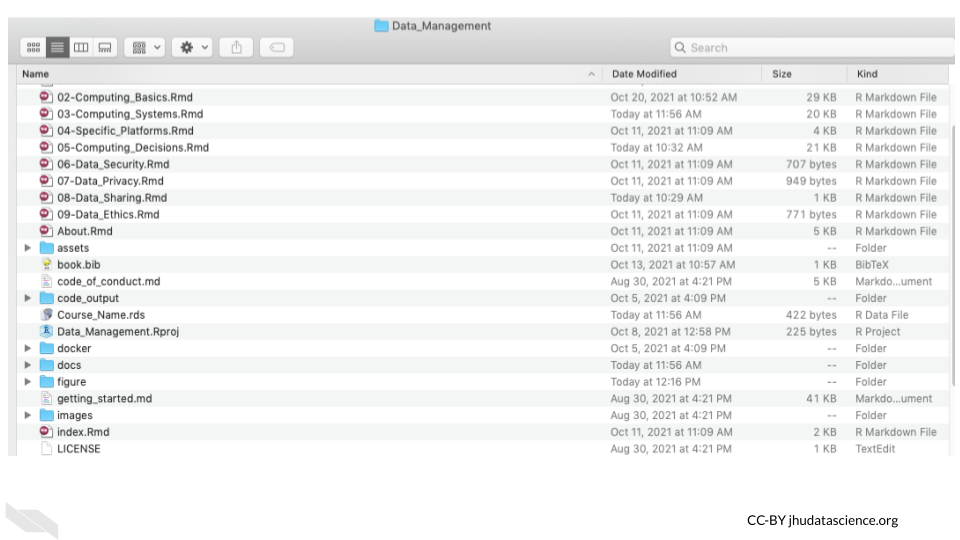

4.3.4 Checking file sizes on Mac

If you own a Mac and want to check the size of a particular file, you can find it by locating your file within a finder window. You can open a new finder window by clicking on the button that looks like a square with two colors and a face (see image below), typically in the bottom left corner on your dock (the strip of icons on your Mac screen) to help you navigate to different application programs.

Once you open a finder window, you can navigate to one of your files.

Once you open a finder window, you can navigate to one of your files.

If you have the view setting that looks like 4 lines, you will get information about the size of each file.

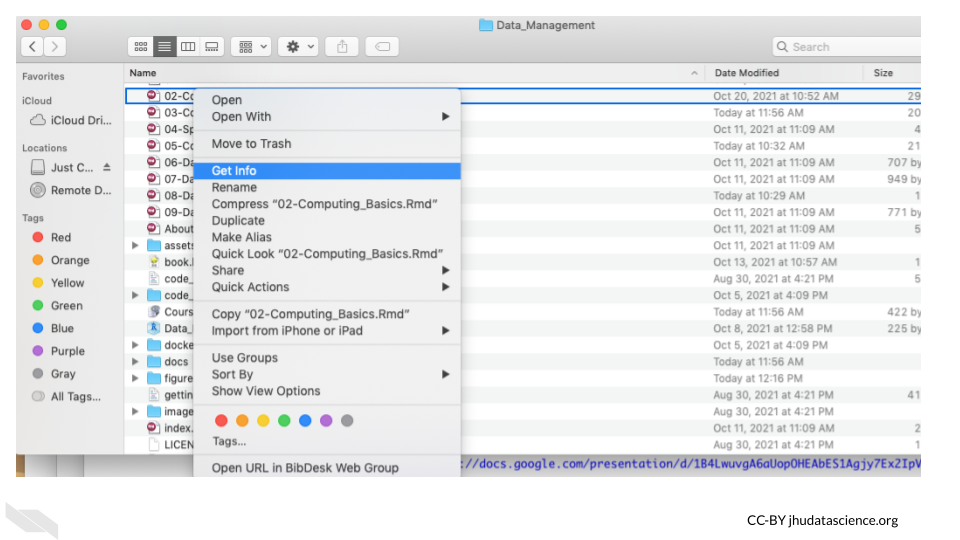

You can right click on a file and click the “Get Info” button. This will give you more specific information.

4.3.5 Checking file sizes on PC/Windows

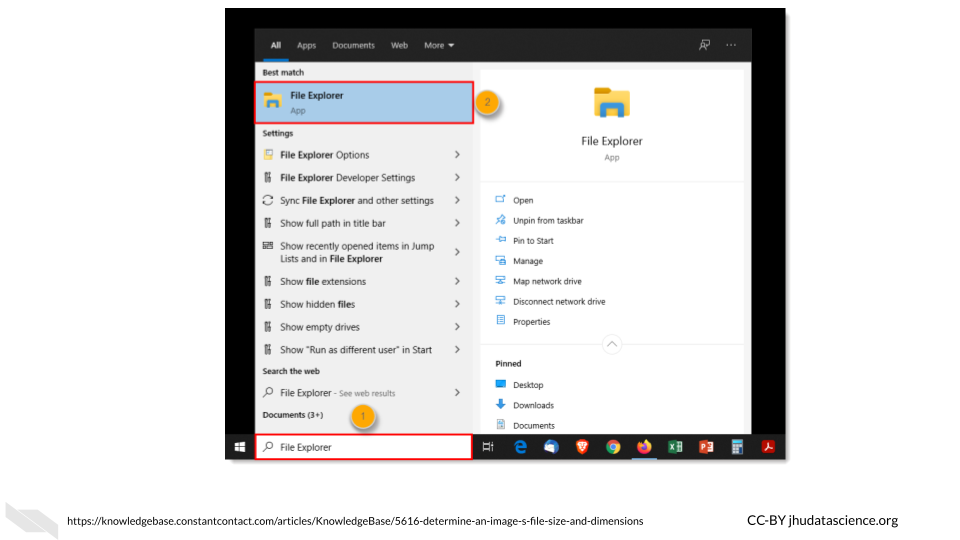

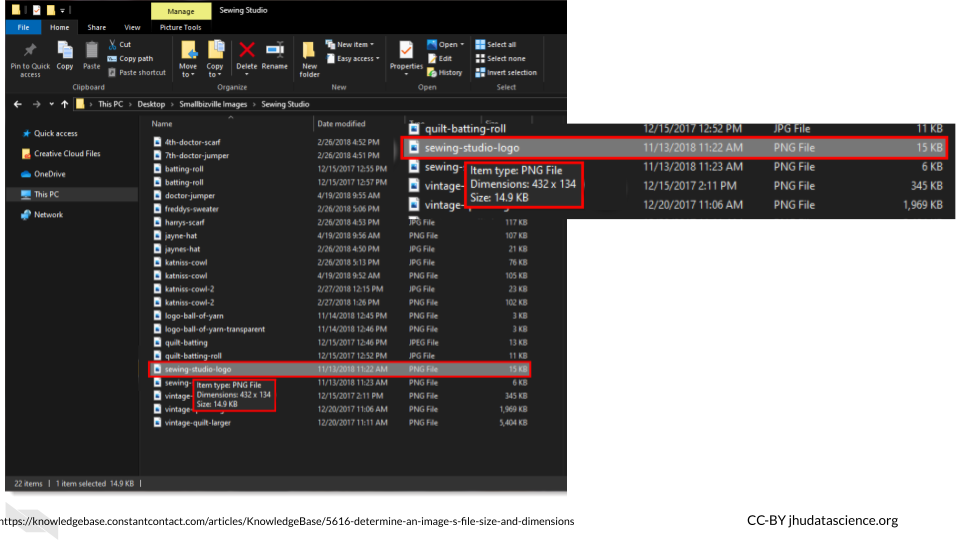

Similar to the process of checking file sizes on a Mac, if you’re using a Windows or PC computer, you can navigate to your files by first opening the File Explorer application by typing this in the search bar next to the “start” button.

Then navigate to your file of interest, which will show information about the size in one of the columns to the right. If you hover over the file name, you will get more specific information.

4.4 Computing Options

4.4.1 Personal computers

These are computers that your lab might own, such as laptops or desktops, used by one individual or maybe a few individuals in your lab.

If you are not performing intensive computational tasks, it is possible that you will only need personal computers for your lab. However, as your project expands and you start working with more and complex data, you might require connecting your personal computers to shared computers for more computational power and/or storage.

4.4.3 Computer Cluster

In a computing cluster, several of the same type of computer (often in close proximity and connected by a local area network with actual cables or an intranet rather than the internet) work together to perform pieces of the same single task simultaneously (“Computer Cluster” 2022). The idea of performing multiple computations simultaneously is called parallel computing (“Parallel Computing” 2021).

There are different designs or architectures for clusters. One common design is the Beowulf cluster in which a master computer (called front node or server node) breaks a task up into small pieces that the other computers (called client nodes or simply nodes) perform (“Beowulf Cluster” 2022).

For example, if a large file needs to be converted to a different format, pieces of the file will be converted simultaneously by the different nodes. Thus, each node is performing the same task just with different pieces of the file. The user has to write code in a special way to specify that they want parallel processing to be used and how they want this parallel processing to be performed. See here for an introduction about how this is done “How to Supercharge Your Bash Workflows with GNU Parallel” (2019).

It is important to realize that the CPUs in each of the node computers connected within a cluster are all performing a similar task simultaneously.

See here for more information (De Doncker and Hussein, n.d.).

4.4.4 Computer Grid

In a computing grid are often different types of computers in different locations work towards an overall common goal by performing different tasks (“What Is Grid Computing? How It Works with Examples” n.d.).

Again, just like computer clusters, there are many types of architectures that can be rather simple to very complex. For example you can think of different universities collaborating to perform different computations for the same project. One university might perform computations using gene expression data about a particular population, while another performs computations using data from another population. Within one location, each of these universities might use clusters to perform their specific task.

Both grids and clusters use a special type of software called middleware to coordinate the various computers involved. Users need to write their scripts in a way that can be performed by multiple computers simultaneously. Users also need to be conscious of how to schedule their tasks and to follow the rules and etiquette of the specific cluster or grid that they are sharing (more on that soon!).

See here and herefor more information about the difference between clusters and grids (Lithmee 2018; “Difference Between Grid Computing and Cluster Computing” 2019).

4.4.5 “Cloud” computing

More recently, the “Cloud” has become a common computing option. The term “cloud” has become a widely used buzzword (Cha 2015) that actually has a few slightly different definitions that have changed overtime, making it a bit tricky to keep track of. However, “cloud” typically describes large computing resources that involve the connection between multiple servers in multiple locations (“Cloud Computing” 2022) using the internet. See here for a deeper description of what the term cloud means today and how cloud computing compares to other more traditional shared computing options (“What’s the Difference Between Cloud and Virtualization?” n.d.).

Many of us use cloud storage regularly for Google Docs and backing up photos using iPhoto and Google. Cloud computing for research works in a similar way to these systems, in that you can perform computations or store data using an available server that is part of a larger network of servers. This allows for even more computational dependability beyond a simpler cluster or grid. Even if one or multiple servers are down, you can often still use the other servers for the computations that you might need.

Furthermore, this also allows for more opportunity to scale your work to a larger extent, as there is generally more computing capacity possible with most cloud resources (“Cloud Computing Vs. Traditional IT Infrastructure Leading Edge” n.d.).

Companies like Amazon, Google, Microsoft Azure, and others provide cloud computing resources. Somewhere these companies have clusters of computers that paying customers use through the internet. In addition to these commercial options, there are occasionally national government funded resource options (described in the next section). We will compare computing options in another chapter coming up.

4.5 Conclusion

We hope that this chapter has given you some more perspective on how large medical research data files can be, and has made you more familiar with how well your computer can accommodate the files that you might work with. We also hope that this chapter has provided you with more awareness about computing options that might be available to you, should you need more capacity than your current computer.

In conclusion, here are some of the major take-home messages:

- A bit is the smallest binary digital data unit. It is a single 0 or 1.

- A byte is composed of 8 bits. File sizes are typically described using units based on bytes.

- A typical fancy laptop today might allow for up to 1 TB of storage; however, this can quickly get used up if you are working with large data files.

- Even if you have enough storage for a large file, you might not have enough RAM to work with a large data file. Your computer might be too slow to handle that type of work. In this case, you might want to consider using shared computing resources.

- A server, when describing hardware, is a single computer (typically a supercomputer) or group of computers that others can share to help them perform more intensive computational tasks or store large amounts of data. People often connect to servers over the internet, but one can also directly connect to servers in a local network (for example, in different offices in a department or a company).

- Computers in a server are optimized for assisting users with computations or storing data.

- A supercomputer is a computer that has much more storage, memory, and computing capacity than a typical personal computer. Supercomputers are generally much more expensive than using a group of more typical computers that together would have the same collective computing and storage capacity.

- There are two general types of servers: clusters and grids. Cluster approaches work by having several computers working on pieces of the same task simultaneously in a method called parallel computing. Grid approaches work by having different types of computers working on different tasks.

- Cloud computing is essentially the use of many servers accessed through the internet. This is often more reliable because there are many servers to use, even if one other users are performing large tasks or if a server goes down. We will talk more about the pros and cons of this option in the coming chapters.

- If your institute doesn’t provide you access to a shared computing resource and you don’t want to use a commercial cloud option, you could consider options like TACC and or Jetstream2, which is a national resource that you can request access to.